More than 30 years ago, the Cold War was ending and we stood at a crossroads in history. Australia was bursting onto the world stage, yet our domestic economy was struggling – a decade of bank crises, a recession we had to have, fears of a “banana republic” and high reliance on offshore funding for domestic investment. But with boldness and bravery, our fragile financial system was reshaped to put some money behind our mouth. Compulsory superannuation built private savings pools to fund upfront (or “collateralise”) our retirements, entrusted to a financial system built around “Four Pillars” to allocate for productive domestic investment.

30 years on, we stand at another crossroads in history. Now a rich nation, we are well positioned to prosper in this emerging world. Sustaining our prosperity will likely require a different approach to how we gather, refine & trade resources, where and how we build cities and infrastructure and how we align ourselves geopolitically. We will also need to back ourselves, move with confidence and ambition, and remain resilient when things might not go our way.

But whilst the bold & brave reforms of the 1980’s and 1990’s achieved their initial goals of stabilising the banking system and building domestic savings, much of our private sector is now struggling. Instead of productive domestic investment, we use our national wealth to fund a three-decade house price boom, record levels of household debt and world-high market ratings for large old companies. At the same time, small-to-medium sized enterprises (SMEs) – 99% of Australian businesses by number, whether family-run or start-ups, driving two-thirds of private employment and much of our innovation – have been largely excluded from our financial system for decades. As the saying goes: getting rich is easy, staying rich is hard.

The role of a financial system is to allocate the savings of an economy to productive users of capital. Capital, whether debt or equity, savings or shares, is often called the lifeblood of any economy. It is better described as an economy’s oxygen – essential for health, activity and growth. Like our own circulatory system, we tend to take our financial system for granted – not noticed when working well but standing out when it doesn’t. Too little or too much savings, allocated incorrectly, sees the underlying economy and its stakeholders suffer. Sometimes imbalances self-correct, other times they don’t and result in crises, as happened most recently in the US and Europe in 2007/08.

When we redesigned our financial system 30 years ago, we made three critical choices to determine who had priority access to the large stock of domestic capital we wanted to accumulate.

First, in our banking system, we established a regulated oligopoly, built around our four largest banks, to stabilise our banking system. We also chose rules that made mortgage lending simultaneously simpler, less risky and more profitable than economically productive alternatives.

Second, in our superannuation system, we shifted the burden of retirement saving onto individuals. To protect disengaged or ill-informed members, we introduced low-fee, low-volatility default products such as MySuper and investment performance tests on superannuation trustees through initiatives such as Your Future Your Super. These made investing in smaller domestic companies more difficult for superannuation trustees, because these assets tend to be high-fee and high-volatility (and often high-return).

Third, independent oversight (through mechanisms such as the Financial Stability Review) is narrowly focused on the financial system and its component institutions, rather than the impact of the system and institutions on the broader economy and the resulting risks and opportunities created. As a result, we tend to respond to issues in the financial system reactively, missing opportunities to inform participants and users, manage risk and adjust rules in real time.

With hindsight, it was predictable that actively increasing the stock of domestic capital would gradually increase local asset prices. Given the choices we made, it should be no surprise that the two largest beneficiaries of our national wealth are the stock of national housing, funded by some of the world’s most profitable banks, and our large mature companies (which include these banks) funded by our large and fast-growing superannuation funds.

But the effects of these choices are fast draining capability, confidence and ambition from productive areas of our economy and the warning lights for our prosperity are flashing brightly.

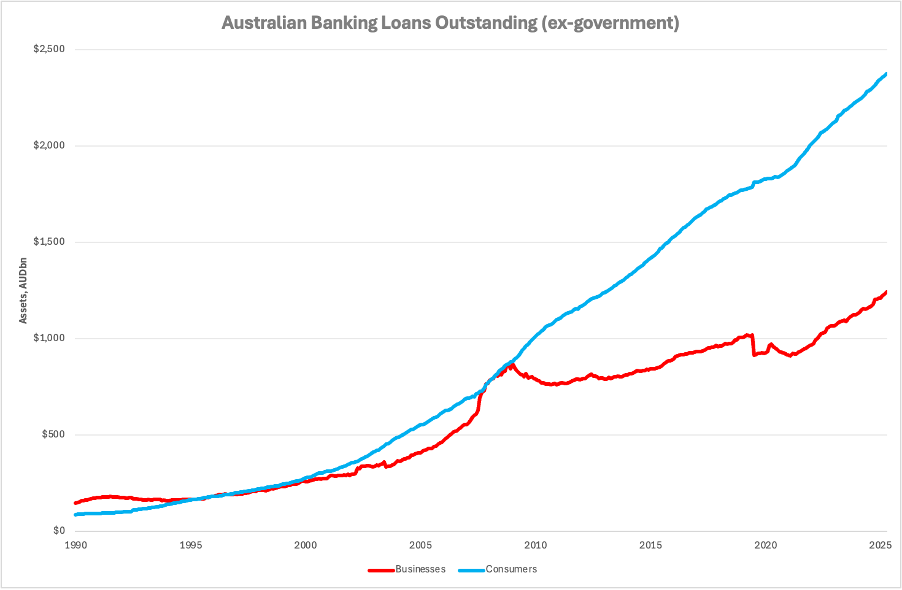

By choosing banking rules that economically favour mortgages over other uses of capital, bank balance sheets have flipped from ~2:1 business to mortgages to ~1:2 and fuelled a decades-long boom in mortgages, household leverage, housing prices and bank profitability.

Source: RBA disclosures (d5)

By choosing to prioritise housing mortgages within our banking system, we have made Australian housing amongst the most expensive in the world - house prices tend to move in lockstep with the size of the mortgage cheque. We justified this choice through an unyielding belief in the “wealth effect” – that homeowners “feeling” wealthier would increase their consumption and always outweigh the constraints of higher property values rippling through our economy’s cost base.

We also believed that more mortgage supply would help first time buyers “get on the ladder”, whereas research from a variety of jurisdictions confirms that higher mortgage supply pushes up house prices and makes things more difficult for first time buyers.

As a result, we face twin crises of housing affordability and cost of living, and just emerged from a 21-month long per-capita recession.

By making these choices, we drove up the cost base of our economy, which generally makes it harder for our businesses to compete internationally. We also limited SME access to our banking system. In other jurisdictions, community / commercial banks, capital markets and non-banks would step in and pick up the slack, allowing smaller companies to access capital outside “big cap” banks or funds. But our banking system remains highly concentrated in the “Four Pillars” and heavily tilted towards mortgages.

Elsewhere, in our superannuation system, ‘low-fee/low-vol’ settings discourage fund trustees from backing higher-cost, higher-volatility (and likely higher-return) assets targeting growing companies. As performance tests measure short-term, listed-benchmark performance, trustees tend to limit their exposure to Australian SMEs. Estimates suggest less than 2% of our superannuation pool is invested in the businesses that drive employment growth, innovation and productivity in our economy, and unfortunately disclosures make it difficult to determine how much of our super (both individually and collectively) is invested into the innovation and employment growth engine of our economy.

These allocations contrast with institutional counterparts elsewhere, who invest a higher proportion of their portfolios into SMEs through venture capital, private equity and private debt and deliver attractive returns for their investors. The net effect is that our SMEs, drivers of much of our innovation, productivity and employment growth, have been undercapitalised and underfinanced relative to property or large mature companies by local institutions for much of the last thirty years and remain so today. By prioritising capital to property or large mature companies and away from SME challengers, we have more concentrated capital markets and industries. This has economy-wide implications for productivity, innovation and economic growth, as well as raising considerable investment risks for retirees.

It’s ironic that the egalitarian idea to democratise investment and retirement through superannuation has benefitted our large established companies relative to emerging ones. This shows on our stock market, where the average age of our largest listed companies is amongst the oldest in the developed world, with 8 of our current top 10 companies on the ASX being centenarians or close thereto. Compare that to the US S&P500, where most of the top-10 companies were SME’s a decade or two ago, as were six of the top 15 companies in China’s leading stock market index. Both of these markets have proactively configured their financial systems, both banking and capital markets, to support growing businesses.

This concentration, whether in industries or capital markets, has economy-wide implications for productivity, innovation and economic growth, as well as raising considerable investment risks for retirees.

Our most valuable company, our “national champion”, is a 100-year-old mortgage utility servicing a market of just 27m people, its market cap exceeding either of the substantially more-profitable global giants Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

Super funds, their members and the broader economy want and need the same thing – strong, diversified returns built off a sustainable and resilient domestic economy. It is not in the interests of the members, depositors or shareholders of our financial institutions, or in the interests of the Australian people, that their “host” economy is hollowed out in favour of old houses and centenarian companies. Yet so it goes.

Ultimately, we are suffering a strain of economic affluenza. It is not Dutch Disease, where external capital flows linked to resource wealth distort an economy. Instead, private savings we accumulated to collateralise our national retirement have flooded domestic markets over decades and distorted asset prices, productivity, employment, innovation and economic growth. It’s certainly not unique to us, as many other high-savings and Basel Accord countries can attest, but we arguably suffer from the most acute symptoms.

It’s an Australian Anaemia, caused by too little economic oxygen making its way to the productive parts of our economy. Like any other anaemia, it starts with mild symptoms that become dangerous and damaging as the condition progresses over time.

There are many areas of our economy that need attention. New housing supply is important for our society but will take decades to deliver. As house prices tend to move in lockstep with the size of the mortgage cheque, new stock will likely be priced just like the current stock without changes to our banking rules. Further, our tax system is long overdue a refresh, and we must reduce “red tape” that inhibits investment and increases compliance costs.

But as we contemplate a future of abundance, it is worth remembering the risks where we ignore our financial system’s pivotal role in our economy. If we keep doing what we are doing, we are guaranteed to get what we are getting – ever-larger financial institutions and savings pools, an anaemic economy propped up by public sector employment and a more-fragile retirement outlook. Our financial system must deliver economic oxygen to where it generates productive returns, not to where it generates rewards to financial system participants with the costs and consequences passed on to the broader economy.

This situation is largely not due to market forces; it reflects the choices we have made, intentionally or otherwise, regarding structures, incentives and outcomes inside our financial system, compounded over many years. History is full of individually rational decisions that, together, produced flawed outcomes, especially in finance. To paraphrase Keynes; the circumstances have changed, we can and should change our minds (and processes).

The good news? Our current condition might be acute, but it is not chronic. Many effective and reasonable responses have been researched and discussed; this piece is long enough already to do that here, but subsequent pieces will focus on solutions. At its core, alongside prudent reviews of supply-side measures and tax relief, we need to ensure our financial system is dynamically structured, regulated and supervised to manage the considerable and changeable risks and rewards that come with large private savings pools. In doing so, there will be trade-offs, especially for financial institutions who have benefitted from these settings for decades.

For the broader economy, there is considerable upside, not just from managing risks better. There is upside from accessing a more diversified pool of investment options, including the returns delivered by SMEs through venture capital, private equity and private debt, and from driving higher levels of growth, productivity and innovation on the economy more broadly. When more of our abundant and long-dated savings can be directed towards productive uses, we improve our chances of a return on our good fortune and hard work.

To paraphrase another old saying, if it can’t go on forever, it won’t. We will eventually address this imbalance, as demographics change and an increasing number of younger people refuse to accept the implications of these choices, and when bond markets sneeze (probably starting at State levels). It’s also likely the large cohort of SME owners and employees will eventually make their feelings known at the ballot box. Hopefully it won’t take a crisis for older Australians to realise that a concentrated economy and domestic investment universe may not be prudent for a resilient retirement. But the longer we leave the situation, the narrower and more fragile our path to future prosperity. It might work, but it’s risky.

However we think about our home, it is an extraordinary country with incredible prospects. We have so much to do, at home and abroad, and we need a productive, innovative and resilient economy to help us do that. To face opportunities and challenges calmly and creatively, with confidence and ambition, will require a financial system that facilitates the flow of our abundant capital to productive uses, rather than prioritising old houses and centenarian companies. Our good fortune has helped us get rich, but it won’t keep us that way. We must now make the choices that can give us a strong return on our luck; for ourselves and future generations.

This is my first substack post. I hope to follow this with a few more to unpack Australian Anaemia, looking in more detail at how we got here and the variety of market-based solutions that can deliver a vibrant, productive and innovative Australian economy. While the focus is on Australia, similar challenges and options face financial systems & economies all over the world (especially Basel Accord countries), as distorted price signals emerge from the collateralisation of future retirement obligations. Get in touch if you have some data / insights you think could be helpful, or where you find something wrong.

Thanks Ivan for sharing this piece. Its provocative reading and instructive to see the change in balance of personal vs business lending since c 2010.

I agree that there has been a shift in focus from investment in productive to less productive asset classes (residential property), whose value is determined more by scarcity than by underlying innovation, technology and/or productivity improvements. If this creates wealth that can be re-invested into other more productive assets, then it could still work, but possibly it gets reinvested back into residential property (maybe new residential property is viewed as more productive if it is increasing the broader housing supply). Be keen to see the data on this.

It does seem there are a few structural challenges enabling this imbalance. I understand that banks are some of the few institutions that are able to create new money not relying purely on savings, meaning they will will always have an outsized impact. Savings vehicles like super funds can provide some diversity of options but likely less impact than banks .

The impacts of this condition are quite a few missed opportunities but also heightened risks. This level of concentration of wealth, capital and debt into one type of asset seems to mean we are vulnerable to shifts in the market. Perhaps if the risks of such a concentration across the whole market is priced in then it makes such assets look less preferable than before too?

This overweight focus on residential property within finance and consequent price spirals also is not just impacting allocation of financial assets. People are choosing careers and life approaches based on these conditions. We’ve heard about reduced birth rates arising from high cost of living and housing. I’d be interested to know whether we’re seeing reduced interest in entrepreneurship as a result of more insecurity of living resulting from higher asset prices which counteracts broader efforts by governments and innovation ecosystem to encourage more business formation.

I’m interested to see your proposals for addressing this. Greater diversity of funding options (challenger banks, PE, VC, crowd) to redirect capital into broader investment proposals seems part, as does helping nudge banks towards a broader investment portfolio (whilst broadly maintaining financial system sustainability objectives). Addressing the imbalance of super funds long-term mandates with short-term reporting requirements may also be part of this. Maybe a broader idea in line with the shift in voting you mention - what would an empowerment and direction of rising generations over finance look like that may put a different lens on these financial choices and what is prioritised across risk, resilience, diversity and long-term impact?

Thank you Ivan. This is an important conversation for us to be having. I was thinking this morning when I read that the EU had just added ADDITIONAL 650B Euros per year to defence spending per year - “What could we do with that much capital if it went towards new industries? How much value could we create?” A great deal is the answer.